With a new jazz festival set to debut in July, we take a look back at jazz music’s ups and downs in New Brunswick’s capital city.

Matt Carter

Jazz music, or at least jazz music in Fredericton, or maybe just jazz music in Fredericton in recent years, has more in common with the likes of punk and hip hop than anything you’re likely to hear on stage any night of the week. Outside of warm weather weekend performances at a local gin bar and the occasional café gig, jazz, for all its freedom and originality, has remained on the fringes of a city that considers itself a minor music mecca.

But jazz keeps knocking.

Like a lot of sub-scenes – those scenes within scenes that cater to a specific audience within a larger music community – Fredericton’s relationship to jazz can be told through a series of up and downs as pivotal figures come and go, get inspired and burn out, or just see their available time to organize, rehearse, and build audiences dry up as life’s larger priorities weigh in.

It’s the same cyclical story all music scenes can relate to. But for jazz (or at least jazz music in Fredericton), the circle is larger than most, which makes each trip around the dark side of the curve a long, exhausting journey. Hats off to those who have held on for one or more rotations. Here’s to the Don Bossés, the Gary Hansens, the Matt Robinsons, and the Jeannine Gallants who have all been part of countless such go-arounds.

But in between these peaks and valleys we’ve had our moments.

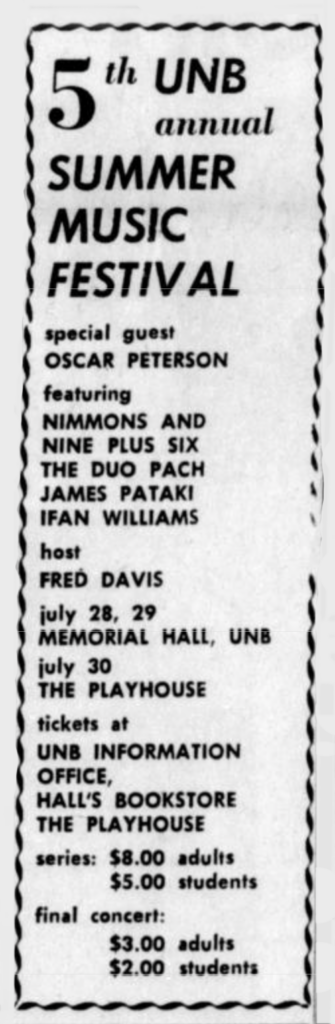

The UNB Summer Chamber Music Festival launched in 1966. In 1969 it became known as the Summer Festival of Chamber Music and All That Jazz, and would serve as a home and an incubator for jazz music in Fredericton for the next 14 years. And big things happened.

In 1970, jazz great Oscar Peterson was a guest performer at the festival. Sharing the world premiere of a new arrangement of his Canadiana Suite, Peterson joined with Phil Nimmonds and his band for two nights of music at UNB’s Memorial Hall before closing the festival out with a show at the Playhouse. For that final show, the air inside the Playhouse got so hot the fire department had to bring in a pair of fans to cool the place down. No joke. That really happened.

The UNB Summer Chamber Music Festival began as a three day event and eventually grew to involve two weeks of programming full of elite players from the worlds of classical and jazz music. After the festival came to an end in 1983, jazz in Fredericton would be largely limited to a couple of small ensembles and performances by The Thomists, St.Thomas University’s long-running big band. In fact, The Thomists have been the one jazz-constant in the city for the last (nearly) sixty years. Formed in 1965, with more than ten albums to its credit and an alumni list that includes well over a hundred musicians, The Thomists deserve much of the credit for keeping jazz music alive in Fredericton.

But jazz keeps knocking.

1991 ushered in the next rise in jazz music’s local popularity with the first Harvest Jazz and Blues Festival. Drawing much of its early lineups from local and regional groups, Harvest would have the biggest impact on jazz in the city for decades to come. By turning a spotlight towards local ensembles like the Cosmic Quartet and Nick’s Dixies to name a few, virtuoso musicians like bassist Lloyd Hanson, guitarist Geordie Haley, drummer and piano player Tony George, and a long list of others including Hans Martini, Brian Mitton, Eric Bourque, Joel LeBlanc and Nick DeVries all became local celebrities in their own way as a new generation of audiences gained exposure and formed an appreciation for the music as a result. Even though many of these musicians had embraced jazz years prior, with a stage to call their own they were now heralded among the city’s best, finally gaining recognition for their art and the years of dedication they devoted to their craft.

Much like its predecessor, Harvest brought in a lot of outstanding jazz performers and curated some memorable events like 1995’s DuMaurier East Coast Jazz Summit, billed as “the biggest jazz show Fredericton has ever seen.” But by the early 2000s jazz was beginning to take a back seat to larger blues bands in the festival’s lineup.

Part of this shift had to do with design. Jazz music’s intricacies often call for quieter venues and stages. The music’s vast dynamic range requires a complementary environment. Noisy tents and sidewalks are less than ideal locations for jazz to truly strut its stuff. This necessity resulted in many of the festival’s jazz performances being relegated to quieter spaces like the Playhouse or hotel ballrooms. Only through occasional pop-up performances were the musicians offered the chance to engage with “outside” audiences who may not have otherwise had jazz on their radar. With the music segregated by necessity, festival audiences were hearing less and less jazz as the years went by. As a result, the demand for jazz performances dwindled as the festival continued to grow and diversify. Due in part to this unfortunate reality, the Harvest Jazz and Blues Festival would eventually rebrand as the Harvest Music Festival. Though jazz will no doubt continue to have a presence at future festivals, the name change freed organizers from the responsibility of having to program a portion of its lineup specifically to serve a small scene within a scene.

The greatest impact Harvest had on city jazz was the exposure it gave younger audiences. By establishing this connection and fostering a new generation of jazz fans, Harvest helped to strengthen and reignite jazz within the local music scene. And although this new generation of jazz musicians and fans remained a tight knit community never gaining mass popularity, this support base would help sustain the music in new ways year round. For many years, The Capital Bar (now The Cap), held regular jazz nights where musicians could drop in to jam a few tunes and audiences could enjoy a mix of standards and improvisations outside of what they might expect to hear during the festival’s fall programming. There was now a regular place for jazz to exist year round. The bar also served as a home for Hot Toddy, one of the most important Fredericton bands of the last 30 years. With its crossover approach to blues music that blended standard ballads (and a growing number of originals) with all the freedom jazz has to offer, Hot Toddy, for a time, was the city’s most popular band. That’s right. Fredericton’s most popular band was a trio playing blues and jazz, or “jazz and blues” if we want to give credit where credit is due, as we should. No joke. This also really happened.

But eventually the jazz nights petered away, Hot Toddy became less active, and the music entered another cycle of hibernation.

But jazz keeps knocking.

A new cycle for Fredericton jazz is beginning. Over the past year or so, occasional jazz nights have begun to happen once again attracting a new crop of musicians and audiences. Players like bassist Jason Flores and sax player Joel Miller are helping fuel this next stage in jazz music’s cyclical Fredericton tenure.

Like other sub-scenes, Jazz music in Fredericton has always followed a “if you build it, they will come” approach. Next month will welcome Jazz on the Wolastoq, a new festival geared entirely towards jazz music, jazz musicians, and jazz loving audiences. And as the next chapter in Fredericton’s jazz history gets underway, longtime players and newcomers alike seem more motivated than ever to explore their passion in new ways.

Fredericton bassist Chad Ball, one of the city’s most active jazz players in recent years, is one of the musicians drawing inspiration from the start of this new cycle. Together with Moncton musicians Denis Surette (guitar), Clinton Fernandes (drums), and Glen Deveau (vibraphone), Ball helped form Luna, a new ensemble focused on expanding beyond the confines of what some listeners may consider standard jazz practice. He loosely describes the band as being, “more ambient or modern or even atmospheric sometimes.”

“Some of the harmony is approached differently and the time signatures might not be what an audience would normally hear,” said Ball. “We do a lot of music by more modern musicians that aren’t necessarily heard very often in a regular jazz gig around here. Also, and this is the best part, we’re writing a lot of our own stuff. So right now I’d say near half our repertoire is made up of original compositions. And we have a lot more ready to add.”

Both Ball and Surette credit German jazz label ECM as a major influence on their new project. With a long list of notable releases by the likes of Dave Holland, Keith Jarrett, Pat Metheny, and countless others whose influence has been cited across all genres of popular music, the label has provided a guiding voice for jazz through thick and thin for over 50 years. ECM was officially founded in 1971, one year after Oscar Peterson melted audiences on a hot July night in Fredericton.

“The concept of Luna was conceived by Chad and myself because of our shared love of that label,” said Surette. “We wanted to start a band that could play some of that material, which is a bit of a departure from playing jazz standards, and at the same time it could showcase our own compositions.”

Next month, Luna will make its debut performance on July 23 at Gallery 78, closing out Jazz on the Wolastoq, the city’s latest celebration of musical freedom and creativity.

As in the past, jazz just keeps knocking.

Festival passes for Jazz on the Wolastoq are on sale now.